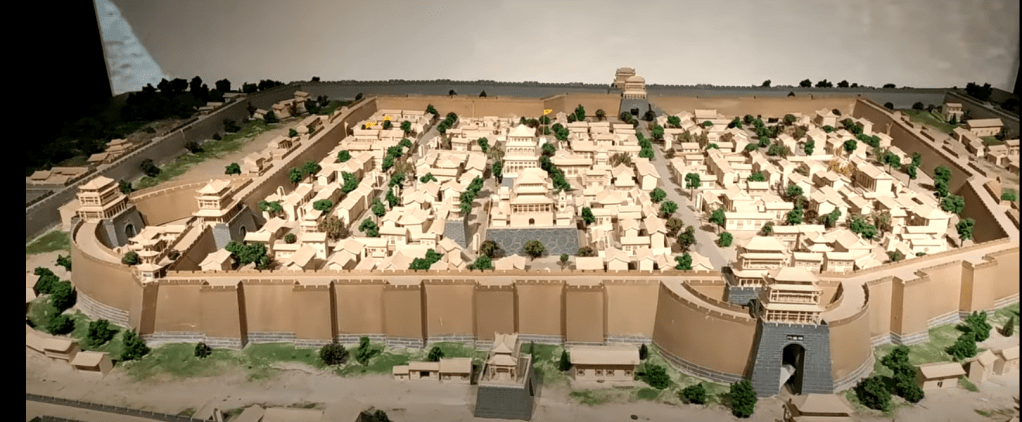

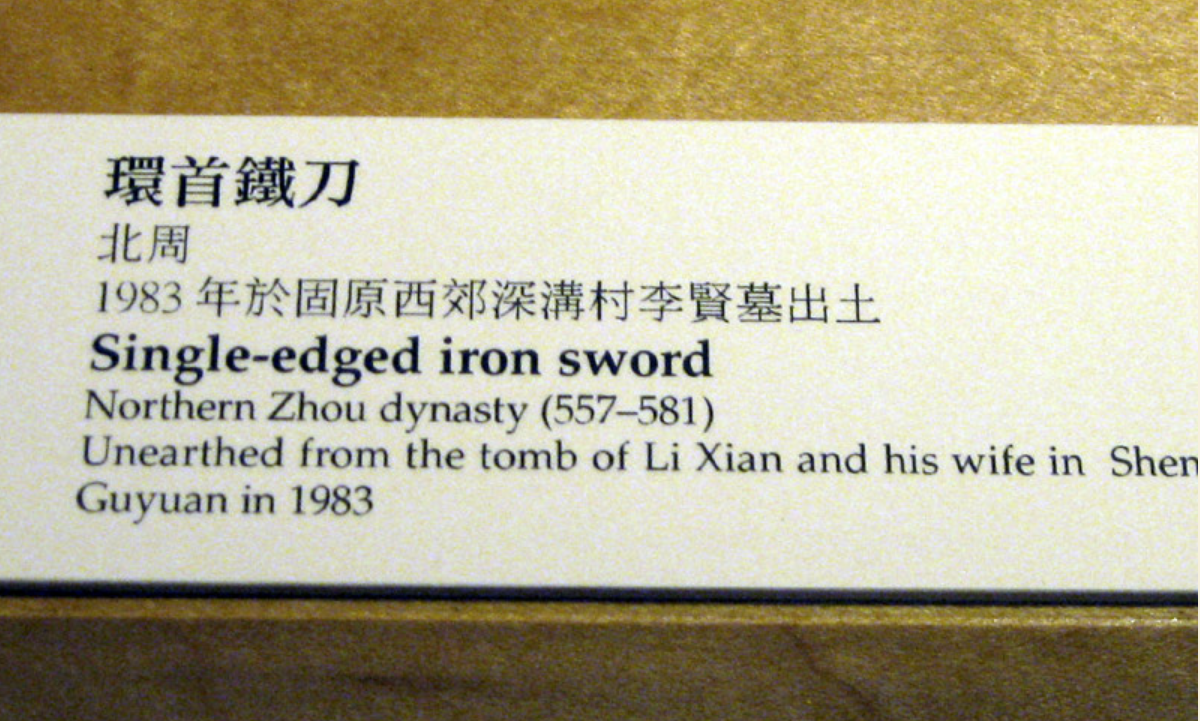

In 1983, in Guyuan, a tomb of a General named “Li Xian” 李賢(504-569 AD)was uncovered in Guyuan, a Northwestern City in China known for its long history and connection to the silk road. the area boasts many treasures from those times. Its museum has a collection of not only Chinese artifacts from the days of the silk road, but also foreign items like roman coins and other objects ostensibly traded between cultures. Within the tomb of Li Xian there are two special items that draw much of the attention; a well preserved saber and a wine pitcher or ewer.

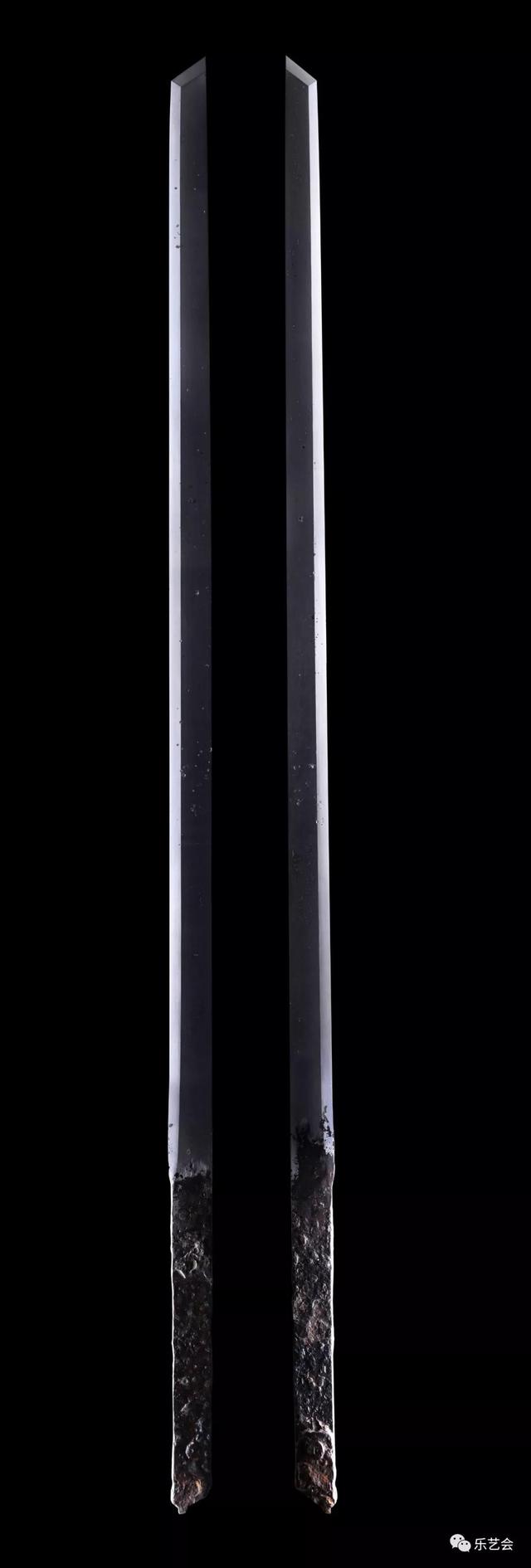

These two items tell a story about contact and cultural influence in ancient China. The sword, a hidden hilt dao or saber that appeared in the Northern Dynasties, in this case, the Northern Zhou. Li Xian was a General for the Northern Zhou, so this was presumably his side arm. It is in very good condition but is so old that it cannot be withdrawn from its scabbard. The weapon design marks a transition in Chinese Dao specifically and military side arms in general. This sword being found in this tomb, gives us a very accurate date for it.

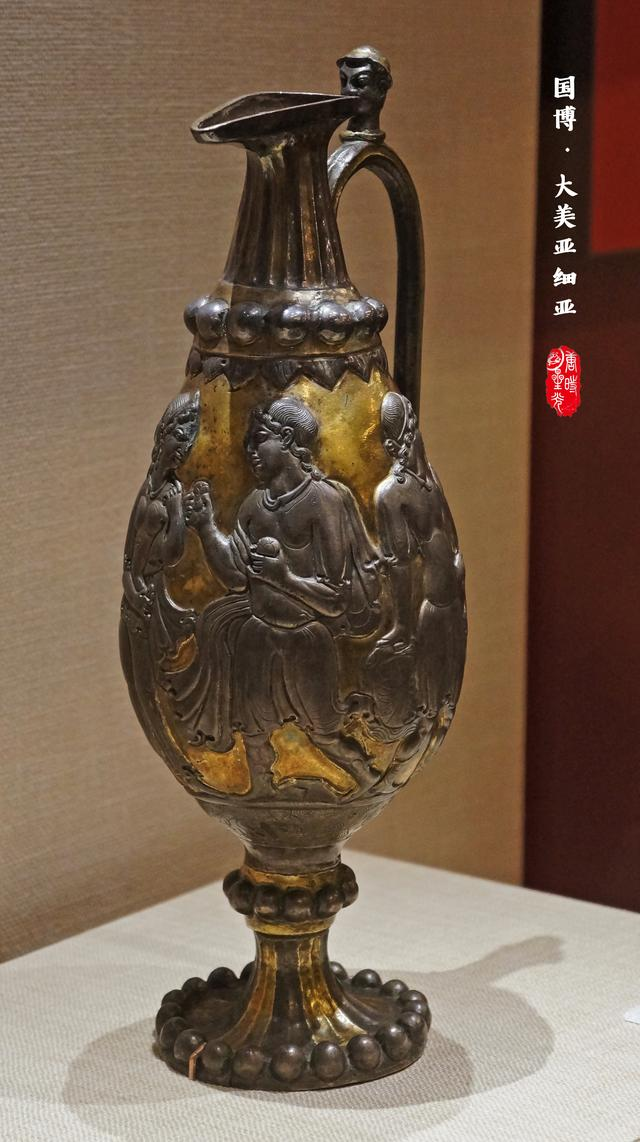

But what does a wine pitcher have to do with this? The vessel its self has been identified as a Sassarian (Persian) artifact and includes art work Depicting the Judgement of Paris. The piece its self is a gem of Persian art being representative of the Sasarian Empire, for which there is relatively little well preserved examples. The “Silver Ewer”, as it is called, is interesting on many levels, not the least of which that it was found in a Chinese tomb. It is one of the only Foreign made objects to be considered a National Treasure of China.

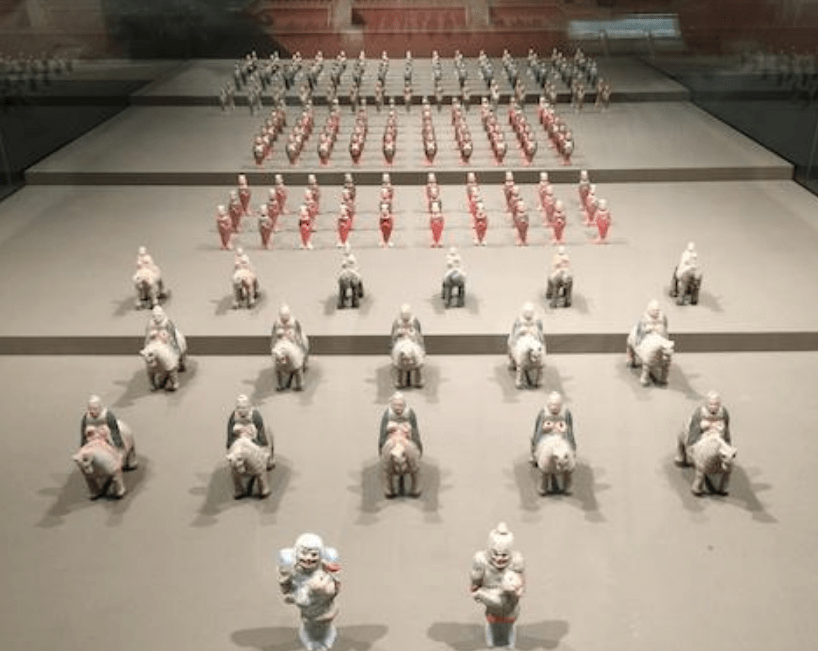

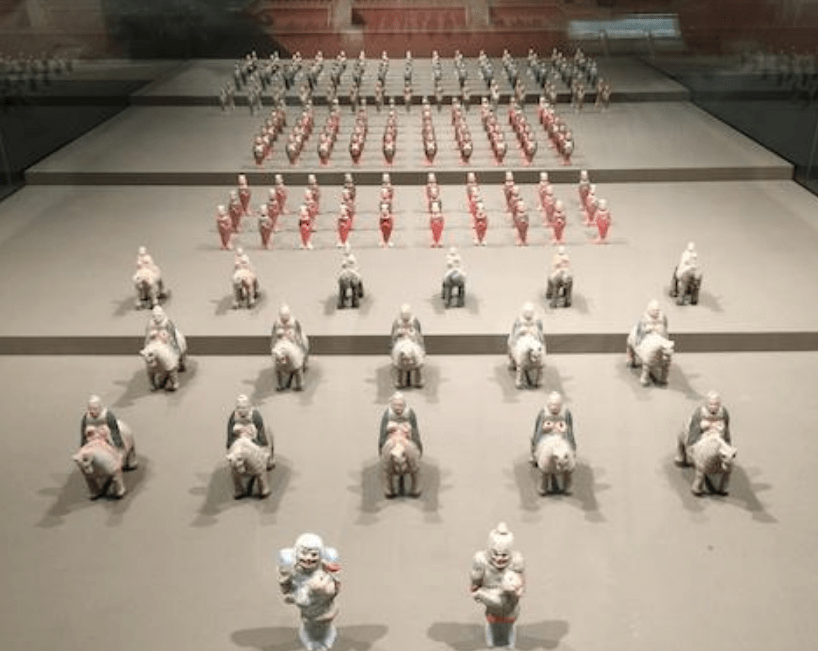

The tomb and its occupant are located at an epicenter of trade during the Northern Zhou dynasty. It is part of a larger complex of tombs that have been untouched by grave robbers resulting in a huge number of artifacts recovered. The contact with Western cultures is well represented from these sites. And this weapon represents a product of the contact. The Ewer and the Sword represent a larger picture of technological and cultural exchanges as a result of the trade on the Silk Road.

Swords and sabers in the late period vs the early

In the Chinese arsenal of cold weapons, swords and sabers occupy a large portion of space in our collective minds. As martial artists, historians, or social scientists we seek to create a narrative out of our experiences. And we like to connect them to our past. Through lineage and relation we tend to see the traditional martial arts as a link to the past and that we are ostensibly training like our ancestors. This, however, is not precisely the case. All of the systems and methods that are practiced today, are modern formulations and evolutions of that which came before. As any system is practiced through the years it adds sophistication, new ideas of training, and new technology. The past practice of martial arts is largely a mystery. We are only afforded glimpses of it through artifacts and stories told of that time. Through many centuries of evolution and change, the form that ancient martial arts would have taken is probably vastly different than what we do today.

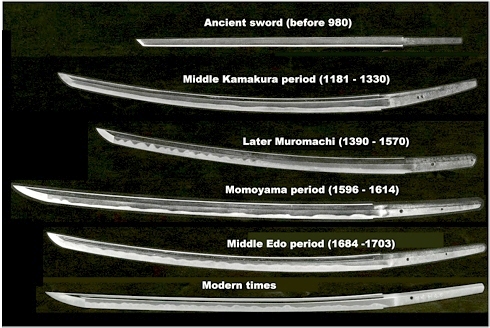

Weapons are a key example. Modern day sword and weapon schools use weapons that take their design and shape from Ming and Qing dynasties, essentially, from about the 1400’s until the 1920’s or 30’s. During this time, many people have noticed a rather small amount of change or development in the shape and over all design of Jian and Dao. Period pieces do not seem to have the same amount of diversity and variety that European weapons of the same time period display. There are several factors for this, but one of them is that China reached a similar hight of sword making and steel production, but did so 1,500 years prior. During this period, (Han Dynasty-200BC-300 AD, through the Tang Dynasty, 618-903 AD) Chinese swords took on a much different appearance than we are used to today.

Jian and dao produced in this time period are famous for being works of art. The forging techniques impressed much of Asia including Korea, Tibet, and most famously, Japan. The forms and methods of sword making show a considerable cross pollination during this expanse of time. Not only do Chinese dao and Jian inspire others, features from Persia and the middle east start to appear on weapons made in the Northern Dynasties period (starting about 386 AD). This period from about 200 BC to about 900 AD represents some the finest craftsmanship on Chinese cold weapons generally and swords specifically. No better example of this is the Hidden Hilt Dao.

A piece of antiquity

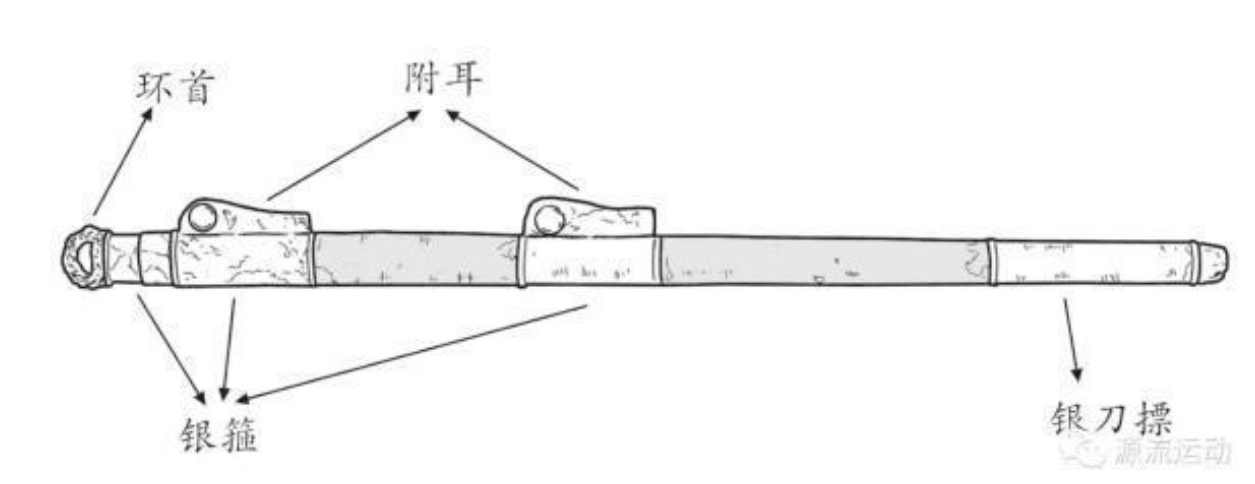

The “Hidden Hilt” style dao is a style of saber that was introduced sometime in the Northern Dynasties (386–589 AD) It has some design features that became standard through the years and the design was seen all the way through the Tang Dynasty. Many of the features are of this sword alone, making it a very unique piece of history.

The main feature of this deign is of course, the hilt/handle. In hidden hilt daos the handle fits into the scabbard all the way up to the pommel architecture. This requires not just good fittings, but precision fit between multiple materials. Wood and brass make up the bulk of the assembly, both tend to change shape with temperature and humidity. This means the craftsman making such a sword would need to be able to accommodate these changes lest the sword become stuck in the scabbard.

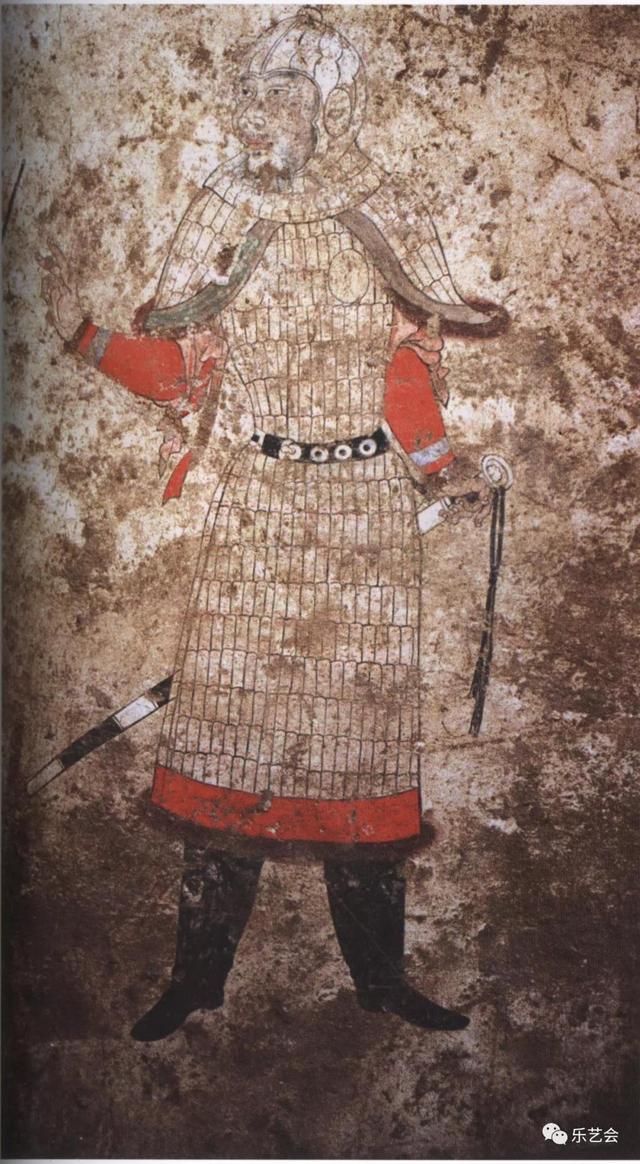

Unlike many weapons of the era, the scabbard of the hidden hilt dao is also tapered. This means that the fitting rings on the sheath must be different dimensions. The attachment method is taken from the Sassanian sabers. This is most likely due to the increased need and use of calvary. The old Han style of single buckle in a belt transitioned into the two loop hangers that became prominent from that time forward becoming the standard until today.

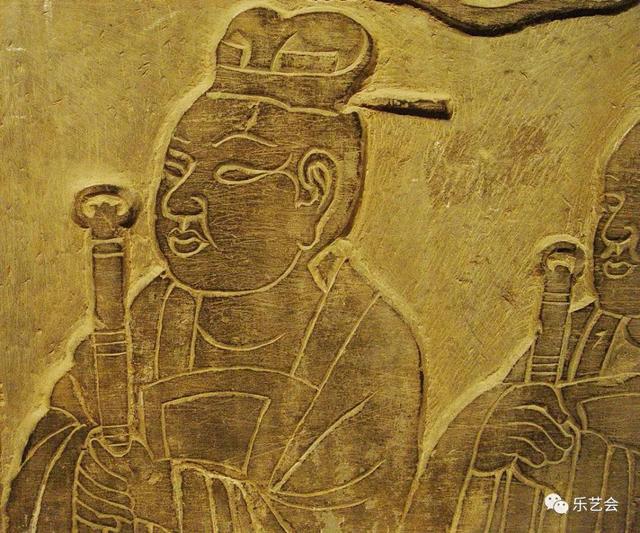

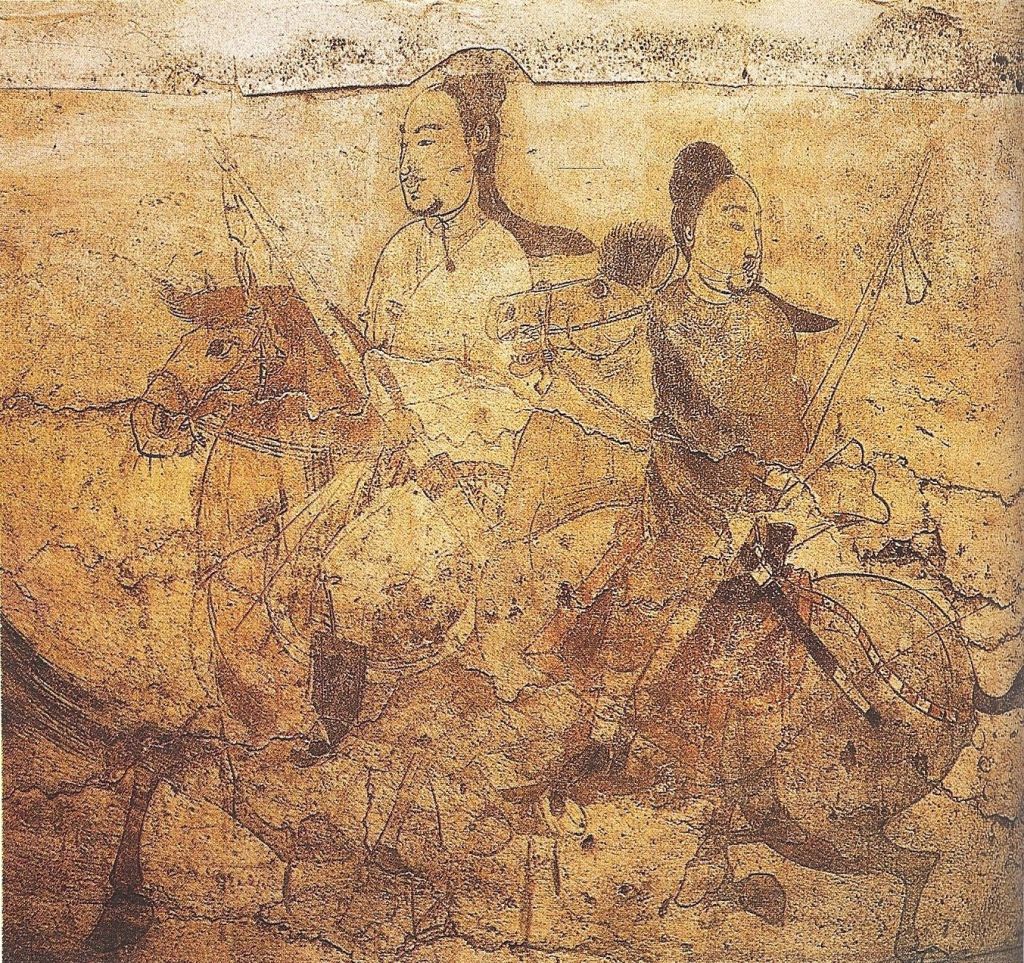

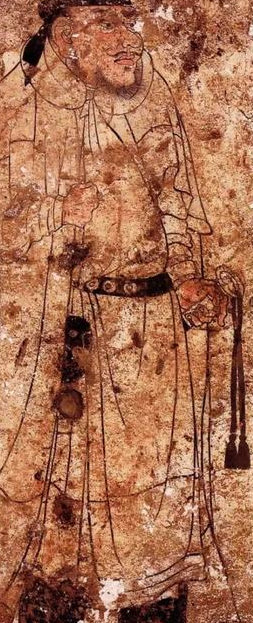

The original weapon was introduced as a calvary weapon, but, that use was not limited to just mounted troops and soldiers. The style of hilt can be seen in paintings and carvings of officials, palace guards, and ceremonial dao. This give us a good idea that the style of sword was popular for centuries after its introduction and it found acceptance in many different areas of combat and utility.

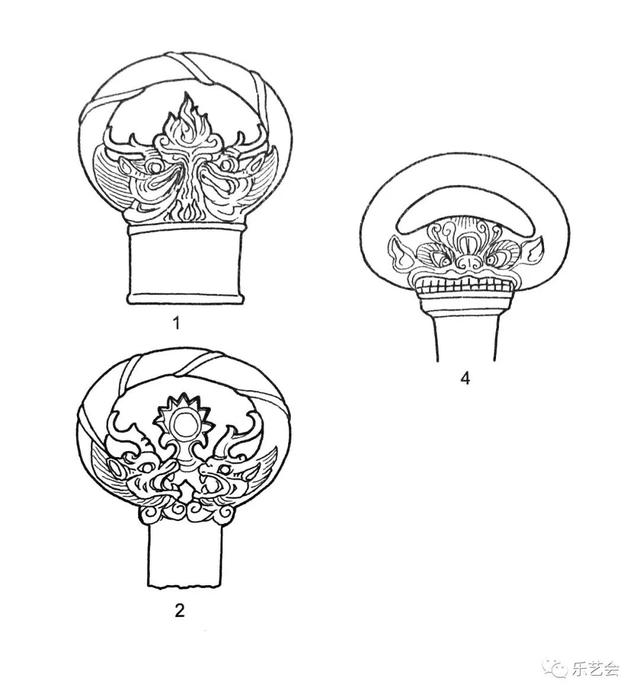

Ring Pommel

Hidden hilt dao and similar weapons all have ring pommels. The ring pommel is a feature of Chinese arms today, being seen on such modern weapons as the Da Dao and Nan Dao. The purpose of this ring pommel is a matter of some debate. While ring pommels probably did have a purpose originally, they had become quite ornate on some examples.

The most likely use the ring pommel can have is for a lanyard. In later model dao in the Tang that do not have a ring pommel, they have a hole that serves as a lanyard attachment. Lanyards can be seen on some depictions of soldiers with these ring style Dao. While we cannot say if this is it’s original, intended, or primary purpose, we cannot say. But it does appear to be at least one use of the ring. We have no depictions of a person wielding this type of dao.

They also function as a hand stop. The handle of these type of dao would , by necessity, be slim. This can cause an issue in control and wield-ability. The pommel architecture does function very well as a hand stop to prevent the sword from slipping out of the hand. Some parties recently opined that the pommel and ring are actual part of the grip, More on that in a bit.

Heng Dao

This weapon represents a sort of transition period in Chinese sword and other cultural items. They began to incorporate and borrow from other cultures they encountered. From the Han, through the Jin and into the Northern Dynasties, the increased contact with mounted forces from the north and the spread of military technology accelerated these influences on Chinese weaponry.

Of particular note for this sword is the two point suspension system. This differs from the earlier single buckle system found in earlier period swords and sabers. As mentioned above, this system became the dominant system of wearing a sword until the present. Even though modern sword are no to be carried around, they still have a sort of faux attachment system included on the scabbard.

Why the change? The Earlier Han dynasty style of wearing a sword was similar to the Japanese method most are familiar with. This being the sword was slipped into the belt or sash vertically and fastened with a single hook or buckle this kept the sword secure and tight against the body. With many the longer weapons being produced during the Han, this method probably started to present problems with Calvary and heavier armored infantry. A long sword tight to the body when in armor or on horseback tends to reduce mobility and increase difficulty of movement.

As speculation has it, the belt slung system is superior for most soldiers and especially mounted troops. The scabbard can hang lower and moves freely to prevent difficulty in drawing the weapon and it allows for free movement of the waist, even in armor. This system classifies these dao as “Heng Dao” “Slung Sabers”. The name literally means “horizontal” or “across saber” but is referring to it being slung horizontally from the belt instead of vertically in or under the belt.

This is where we return to the tomb of Li Xian and his dao found there. This extremely well preserved example of a hidden hilt dao was found with the “Sliver Ewer” from the Sasarian Empire. The presence of both a hidden hilt dao of this design and the Persian vessel, demonstrate the cultural exchanges happening at the time. The fact that Li Xian is known to have lived during a certain time gives us positive dating on the weapon and at least a period that we can assume the Persian style belt hanging system had proliferated back then. The fact that this tomb was so pristine and untouched has given us a rare glimpse into the vibrant time period represented.

Reproduction of history

There are frustratingly few surviving historical examples of these dao. Those that we have are often too degraded by time and corrosion that they are no longer functional. Fortunately for us, LK Chen is recreating these historical weapons from existing examples. The Hidden Hilt Dao (Called the Dragon Sparrow on their site) is a fine example of something that has been missing in Chinese martial arts for too long; historically accurate weapons. Lk Chen designed his dao on an existing specimen that somehow is still functional. With period accurate techniques, but modern steels, the Dragon Sparrow is a fine reproduction and a very useable weapon.

That allows us an opportunity to investigate the qualities of this blade and try to reconstruct useable techniques from them. It also gives us a nice experiential window into the weapon and how it feels, performs, and stands up to abuse. We can actually use the weapon real time and figure out possibilities from that experience. (Ben Judkins has done an excellent review of this sword on his blog and here)

Wielding the hilt

Because of the hidden nature of the hilt assembly, the handle is very slim. When using a historically accurate reproduction from LK Chen, some of the difficulties do present themselves. Some of these are due to modern anatomical variations of size hight and hand size. Some them are due to the various design features in the weapon. These dao have no hand guard to speak of. For obvious reasons, a hand guard cannot be a part of this style of weapon. But that does present an issue. The slim nature of the handle and the absence of the guard increase the chances that one’s hand is going slide up on to the blade.

So, the question for modern practitioners and sword aficionados, is “how do you hold this weapon”? While holding it in the hand on the handle feels the best and most natural for what most of us are used to, some find holding it by the pommel assembly, and using the ring as a contact point for the back of the hand. This leaves a bit of the handle protruding in front and moves the balance point up away from the hand.

These dao are obviously slashing and chopping weapons. In whatever grip you use, it seems fairly clear that thrusting was not a high priority for designers of these dao. So we can surmise that the movements being done will include long slashing movements and shorter chopping ones. So, holding it at the end of the handle does work. It also solves a problem of drawing the sword without having to move your hand on to the grip. It is also of a greater girth than the grip of the sword that must be fit into the scabbard. Holding on to the back part of the hit does offer more surface area to have contact with. So a totally plausible method.

The difficulty in answering this question is that there is no real evidence from the period, in the archeological record or the artistic record, of people wielding the hidden hilt dao. All of its appearances in art have show it in the scabbard hanging by the person’s side. We also have no training materials or writings on this weapon (or any) from that time period. So it is left up to us to guess.

On the other hand, the balance of the sword is much more nimble and friendly to wield when holding the handle than holding it by the pommel. There is grater control over the weapon, the balance is easier to deal with, and chops can be given a little more “pepper” with the point of percussion a bit more under one’s influence. Also, there are some historical examples, in paintings and actual specimens of these handles with shark or ray skin wraps on them. The only reason to have such a wrap on a sword who’s handle is concealed in the scabbard is for grip. And indeed, in my various experiments with the reproduction, even a leather glove improved the handling of the sword.

The Mystery persists

At the end of the day, the mystery of the Hidden hilt Dao is the same as the mystery over all swordsmanship from the time. We can see that the period produced some exquisite swords and metal working technology. We can also see from the archaeological record that dao and Jian were popular items and that fencing had at one time been a very common past time. But this is about all we have. No training manuals or military treatises exist that contain explicit instructions on these or any weapon or fighting art. They must have existed in some form, but through the ravages of time, none are known to exist.

The period we are discussing was a very long time ago, around the time of the migration period in Europe, and very few period artifacts survive today. The ones that do are often fused in their scabbards or rotted away to not much more than a corroded blade and some fittings. We are beyond fortunate that we now have a maker like LK Chen that is creating these weapon reproductions to as closely mimic the examples that we do have. Through the use of these reproductions, we can actually feel how they perform. We can see how they move and discover things about them that might allude academia. This closely mirrors the act of “experimental archeology” where we try to discern the function from the form.

The Hidden Hit Dao is a marvel of ancient technology. Museum worthy pieces of martial history. Their craftsmanship was famous even in their time. LK Chen has very faithfully reproduced this weapon for modern practitioners and collectors. I look forward to much more discovery and discussion of these another often forgotten Chinese arms. The Tang saw the advancement of many technologies and systems. Dao from the period are gems awaiting a viewer to marvel at them.