One major difference in the historical armory of Europe versus China, is the prevalence of double edged straight swords. Jian as we call them, are the main stay of European sword arts all the way up to the 20th century. In China, for the majority of its history, the single edged Dao has reigned supreme. The jian still holds a place of esteem and reverence, but the dao has been the work horse of the military and warfare, as well as civilian defense and aggression. If we look at the archeological record, we see a quick transition from a Jian based culture, to a Dao based one. The transition is faster than most realize, and one weapon (or style of weapon) can be reasonably called the one that started it all. Why was it so influential?

The answer, as unlikely as it may seem at first, is horses.

Horses in China

As far back as the Shang (c. 1600 – c. 1050 BCE) and Zhou (c. 1050 – 256 BCE) periods, Chinese warfare has included horses. In the early days, these were used to pull chariots, the principle piece of military technology at the time. True mounted calvary did not appear, according to some scholars, until the 4th century BCE.

With the development of calvary, the evolution of horse riding harnesses and saddling followed the need. As the use of the chariot waned, the need for more sophisticated harnessing for the rider was required. The Warring States era (402–221 BC) saw the development of the breast strap harness for the saddle. This is quite a big step forward and scholars are still divided on to the actual sequence of events that led to it’s invention.

The way horses have historically been harnessed to pull weight is similar to the way oxen and other beast of burden with a yoke around the neck. The issue with horses is that they do not have the shoulder bump on their back to hold the yoke in place. As a result, a system that used the belly portion and a neck harness was used. This had the effect of compressing the horses windpipe, reducing its capacity to pull. It can bee seen in the art of the Han, that horses are depicted as carrying up to six persons in a cart. The supposition that this would have required the breast strap harness to allow the horse to breathe unobstructed.

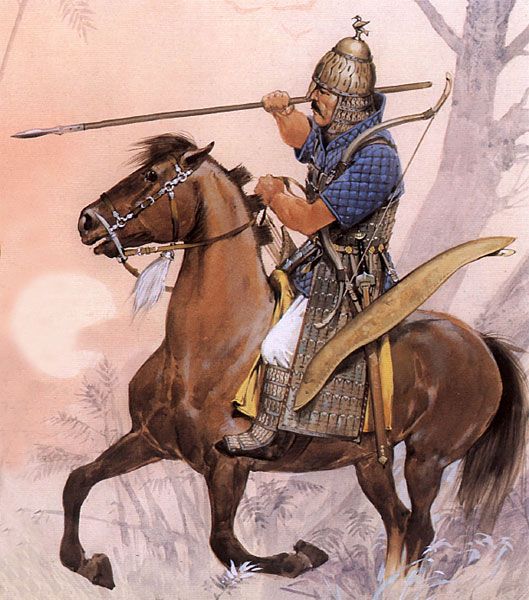

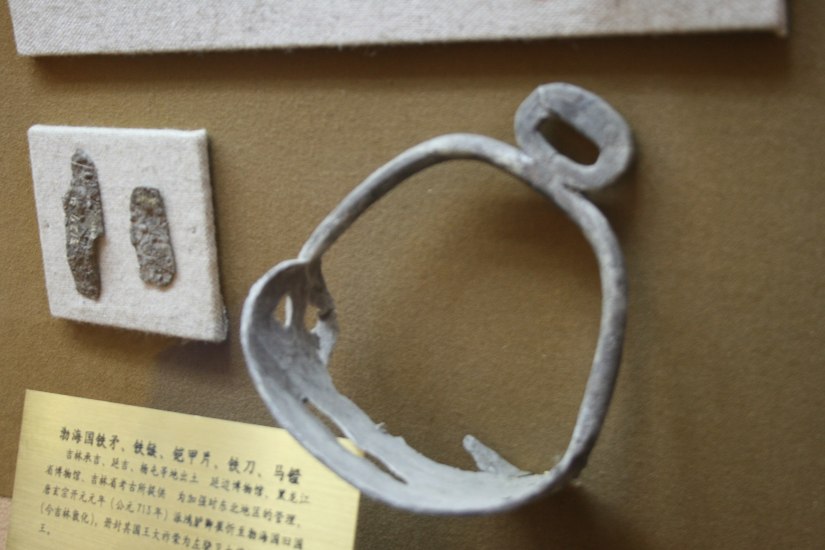

More advancements came through the Han Dynasty. Bridle and saddle systems allowed more freedom on top of the horse. This allowed for the use of weapons like the halberd (Ji and Ge configurations) as well as spears and lances. It was not until at least the later Han that stirrups begin to appear. First as a single “mounting stirrup” on one side to allow the rider to mount and then transitioning into the familiar double sided stirrup by the Jin dynasty (266–420).

The Heavenly Horse

During this period into the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) the main breed of horse used was the Central Asian/Mongolian type of horse. These horses were not that fast, but had strong barrel shaped bodies and short legs, making them powerful and stalwart in endurance. As Horse warfare transitioned form Chariots to Mounted calvary, speed became more of a priority. It is generally accepted that the speed of the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE) calvary was instrumental in its success.

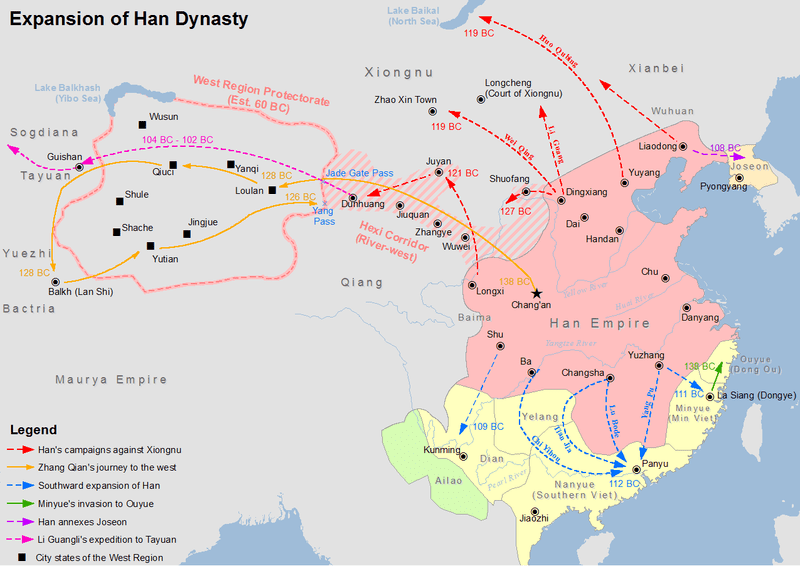

This changed when the Han made contact with the Dayaun-大宛 civilization of Persia. Ferghana Valley which was located in what is now modern Uzbekistan, had a breed of horse that were far superior to the mount that the Han Army was using. After many years of defeats and assaults from the Northern Steppe people Xiongnu, the Emperor Wu Di decided he would obtain these horses to aid in the effort to fight them. These horses were fast, powerful and superior to the Central Asian breed for riding. These horses were called “Tian Ma” or “Heavenly Horses”.

The Han had had contact with the DaYaun for years before. Both sending envoys with tribute gifts to each other. The Dayaun brought their horses and they became the major commodity from the area. The Han began to import the Ferghana horses and soon were doing it at such a rate, the Dayaun stopped all export of horses to the Chinese. This simply empowered the emperor to launch a full on incursion into their lands. From 104-101 BCE Han- Dayuan war raged with the Chinese becoming victorious. From then on, Ferghana horses were imported and bred by the Empire to create the ideal horse for the Han calvary. This concerted effort to improve the calvary in response to the Northern threat can be considered one of the earliest examples of an arms race.

Death of the Chariot

With the transition away from chariot warfare, new tactics and weaponry needed to be developed. The Han calvary had traditionally used Long weapons like Halberds and spears along with Jian as a side arm or main weapon. Both of these weapons pose some logistical limitations to a rider. Long weapons were cumbersome when in close and using against another mounted soldier. Jian of the Han are long and thin, good for thrusting but less so for slashing and chopping. Also, the thrust of a sword can become stuck in the target, rendering it a liability to the rider.

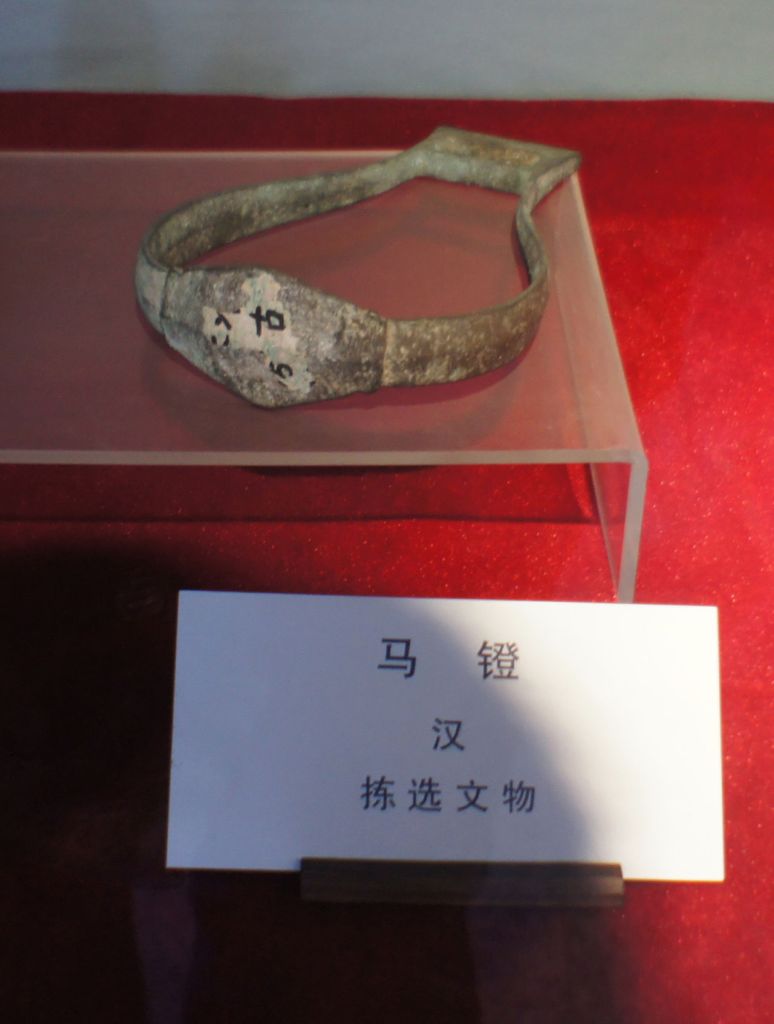

And this is where the Han Ring Pommel Calvary dao comes in. The weapon appears around 100 BCE and was used successfully in the Han war against the Xiongnu 匈奴 in the north. The weapon is much different than the other Han weapons created during that time. It and its infantry counterpart, are a departure from the Jian that began a 1000 year migration in the Chinese arsenal toward single edge swords and the supremacy of the Dao.

But the time of the Han, steel had been adopted as the standard material for swords and weapons. Bronze arrow heads, shields and daggers still found some manufacture, but because of the weapons of the Han, steel was often more valuable than gold. The advancement of metallurgy gave the kingdoms of Han, Qin, and Chu a metal that could produce long, light blades that were flexible enough to withstand abuse and return to true. It enabled the experiments with blade geometry to discover the properties of different forms and shapes.

These are the ingredients in our recipe. The Han had a problem in the Xiongnu that needed to be solved. The technology and materials were available to advance both horse harnessing and blade manufacture. The stage was set for the entrance of new technology that would change warfare.

Blade shape

The Han Dynasty Ring Pommel Dao has a unique blade shape. The calvary version is very long, has a pronounced recurve, and a hollow grind down the length of the blade. This gives it a strong cross section and the ability to put a thick spine behind a razor sharp edge. There is not much need for thrusting with such a weapon, and the design of the blade is hallmark of a cutting and slashing weapon. While you could stab with the tip, it is more likely that it was intended to slice through and be dragged across the target.

Knowing that the Han were embroiled in their war with the step horsemen, who often out did them on the battlefield, and went as far as extensive horse breeding projects to develop better mounts, it is not a far leap to imagine the saber was developed in much the same way. Archaeologists and historians are not certain where the design first arises, but the earliest example of a ring pommeled blade in this shape is a short knife used at the time for cutting bamboo. It is supposed that this knife provided the shape and beginnings of this rather sophisticated weapon.

Recurve vs Curve

The most interesting, or at least the most unusual, feature of this sword is the fact that it has a “recurved” edge. This means the the cutting edge is on the inside of the curve of the blade and not the outside as more modern saber were eventually made. This feature is one that is found on several bladed weapons in many cultures, but the most famous is probably the Kukri.

Any type of curve succeeds in lengthening the edge. This can be done to make chopping and slashing more effective and easier. A regular curve will allow for slashes that can be recovered from very easily and will focus force into a smaller area of edge when chopping. A recurve does something similar but also different. The recurved edge will have much more contact with the target as it is pulled through. Where as the regular curve follows the arc of the swing allowing for long cuts across, the backward curve can slice more effectively and deeper. The edge geometry can give it a powerful chop as well.

The material these weapons were made from was also critical. Steel allowed blades to be forged much longer and lighter than bronze, thus giving the calvary dao the next advantage; length. Length is often though of in terms of reach, and here is no exception. Looking at the length of these sabers gives us a bit of an idea of how they were used. When we think of horseman to horseman combat, that can come in handy. But also there is the added force that is produced from a longer lever. This makes longer weapons more efficient in producing power and as long as your blade is well constructed, that power can be transmitted to your target.

Speculation and experimentation

Up until recently, reproductions of this weapon were few and rather expensive. LK Chen has created a reproduction of the dao for modern martial artists and enthusiasts. Being able to handle a reproduction as accurate as the ones made by LK Chen is a boon to all martial artist and historians etc who have an interest in this things. From a martial artists perspective, it is always good to look back at the path things have taken to get to you. Often that path is far more involved and interesting that anyone would have imagined. And while the techniques have been lost, the weapons still remain, so there is hope to find some semblance of how they were used.

It makes a modicum of sense that the original design was taken from a agricultural or utility knife. The recurves very common on such knives and cutting implements is far more common. Sickles, scythes, skinning knives, all commonly have received blades. This increases their cutting and slicing utility. However, in swords, the recurve may not be as useful or at least not as obviously superior to a regular curve as in later weapons. The sharpness of edge, blade cross section, and action of the person wielding it are often far more important to a weapons ability to cut.

In quick subjective tests, the recurve blade does not have much discernible advantage over the regular curve. At least with a weapon this long. The handling characteristics are similar enough so that it feels like what a saber generally should fee like. It would be able to be used by almost anyone with the same. So far we have been limited to various regular testing methods of the sword. The next step is to have someone trained in calvary techniques and is a suitable horseman to try it out in context. So stay tuned for those developments.

What happened to Dao design?

While the recurve was used on both the infantry and calvary dao in the Han dynasty, it seems to have been largely abandoned in subsequent dynasties. At first, the move was to a straight blade, no curve or recurve. More than likely, it was discovered that the thickening of the spine and geometry of the blade leading to the edge were far more important factors in designing an effective weapon. Contact with other cultures through the silk road also created many influences and cross pollination of design and use of weapons. The Han Dao, with its long slender recurved blade was replaced with shorter, straighter dao with a thicker spine and a more wedge shaped geometry.

It is unclear why this happened. While it is almost universal that the development of swords and metal weapons follow similar paths, this design was completely replaced. Some features, like the ring pommel, follow the dao until present day. Others have fallen by the way side. It could be that shorter straight dao, while being used with stirrups, offered more flexibility in use. Being suitable for both infantry and horse back. But it is also notable that the curved saber, most common shape of saber used from horseback, did not really catch on in China until the Yuan dynasty when they were under Mongol rule. They had contact with curved sabers from as early as the late Han, but the straight dao persisted into the Song. It could be that the benefits were deemed not large enough to add to much complexity to the design.

Depending on what our next tests show, it could be that the advantages to this weapon shape, do. not equal the time and effort it takes to forging, sharpening, and maintaining a recurve blade of this size. Ancient people could have found that more useful changes were to the cross section and edge angle. It is hard to tell this far after the fact.

Conclusion

The Han Dynasty calvary dao is an impressive piece of military technology. China was an “early adopter” of steel in weapons, with steel taking over the landscape extremely quickly replacing bronze, and metallurgy, horse breeding, as well as mass production and standardized forms, created some of the most advanced and sophisticated weapons in the ancient world. This was the “skunk works” of the ancient world. Focused development of arms, armor and strategy.

But when looking at weapons like this we must remember, so much time has past between then and now. And when trying to make sense of things from as far back as the Han that was over 2000 years ago, we have very little left to guide us. So we try it ourselves. As I said before, I am not a horseman or have I tested this in that context, which of course, is what it was built for. But using what I feel from using it on foot, the features that make it seem to be a great choice for mounted combat are fairly obvious once it is moving.

This is it. The weapon that started the transition from Jian to Dao in the Chinese arsenal. A beautiful piece of antiquity. I anxiously await some trials of this weapon from horseback, this will hopefully open a while new line of inquiry and discovery. Please stay tuned for developments!

Further reading:

The horse in Early China: http://imh.org/exhibits/online/legacy-of-the-horse/horse-early-china/

War with the XiongNu: https://weaponsandwarfare.com/2016/10/18/xiongnu-vs-han-200-bc-ad-4/

2 thoughts on “War of the Heavenly Horses: the origin of China’s most signature blade”