During the Ming Dynasty (大明1368–1644), China minted coins that it sold and traded throughout the Asian world. These coins, very familiar today as “Feng Shui/I Ching” coins, were accepted currency in much of the south East Asian world. The popularity as being a relatively stable form of currency accepted in many locations lead to an increased production in China. These were traditionally made of some manner of copper alloy, and the traditional mines for copper in provinces of Jiangxi, Shaanxi, and Shanxi. Places that did not have copper available to them were asked to donate copper items to be smelted down for the minting of these coins. By 1393 there were 325 furnaces minting coins for distribution within the Ming and their vassal states and trade partners abroad. As the Dynasty continued, production of the coins became such that the Ming Court needed to import copper and other metals from trading partners and surrounding nations. This included Japan where copper was one of the chief commodities exported to Ming China. This ore was then used to mint more coins to be eventually bought back by the Japanese.

The Ashikaga shogunate (足利幕府, Ashikaga bakufu, 1336–1573) during its reign, imported many of these from coins China. Since official Ming coins had standard weights and measures for value, they were used as the main currency within Japan. One coin being mon, (文) and a string of 1000 coins equaled a kan (貫). Japan relied so much on these coins and their value and availability that they were sometimes the single item that Japanese merchants wanted in trade. The Shogunate knew the more coins they had in circulation, the more robust and healthy the economy tended to be. So, the impetus for Japan to trade things of great value would have been palpable by leaders of the time.

The Japanese have had a strong trading relationship with the Chinese since as far back as the first century AD. The Book of the Later Han or Hou Hanshu (後漢書) written in the the 5th century, records the Japanese had contact in about 9-169 AD. But it wasn’t until the official unification of each of the nations in the 6th and 7th centuries that Japanese emissaries visited the Sui and Tang Dynasty for the purpose of obtaining technology, political systems, philosophy, and other social and cultural products for which China was far more advanced. Many artifacts from these expeditions can be seen today in the treasure houses of places like The Shōsō-in (正倉院) of Nara in Japan.

After the defeat of the Mongols and the institution of the Ming Dynasty, Emperor Hóngwǔ (洪武, 1328-1368) instated the Haijin, or the “Sea Ban”. This was a general embargo of maritime trade to be regulated by the Ming Court. Those wishing to trade with Ming China needed to present a tribute of goods to the government to obtain a license for maritime trade. This system, while expensive and time consuming, was never the less, profitable for the merchants and traders, which caused the Emperor to forbid all trade with foreigners when this came to his attention. This did nothing to stop trade, but did succeed in driving it underground. This ban was later lifted on foreigners although the tribute system and sea ban remained in tact up until the early Qing.

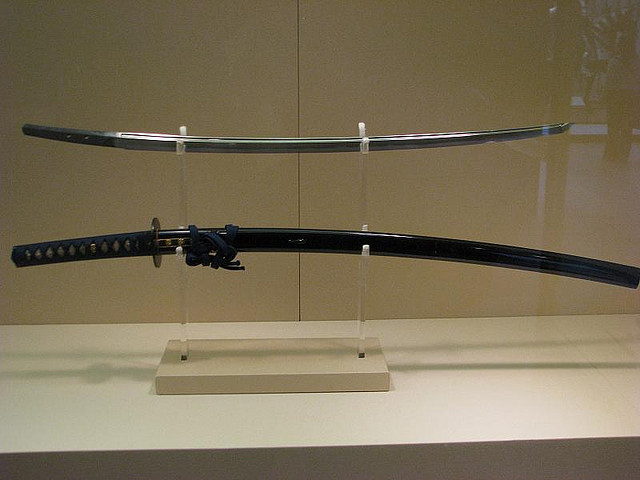

Tribute missions would be chances for traders and merchants to meet with the Ming officials and make the exchanges of goods. Tribute goods were essentially the gifts and fee for the privilege of trading. The exchange goods and supplementary goods would be the cargo that is up for exchange. Records show that the first tribute sent by Ashikaga Yoshimitsu was in 1401. It consisted of 10 horses, 10,000 sheets of paper,100 fans, 3 screens, 1 set of O-yoroi 大鎧 armor, 1 set of domaru 胴丸 armor, 1 katana, 10 Tachi swords, 1 ink stone and 1 desk. The armor and the swords will stand out here. The second mission two year later contained 1,000 yari spears and 100 Tachi swords.

And these were just the tributes. As the years continued, Japanese swords began being imported in greater and greater numbers and were becoming more valuable. The popularity of Japanese swords in Ming China caused the Ming court to accept only 3,000 swords for each tribute mission. When that did nothing, they reduced it further, eventually limiting sword imports to be only 375 pieces per trade mission. Also, the court lowered the price they would pay for swords. In 1432, Japanese records indicate that the cost of production for one Taichi sword was 800 to 1,000 mon but sold for 10 kan. However, in order to slow import, the Ming reduced the price in around 1483 to only 600 mon per sword, and by 1511, the price had finally dropped to 300 mon. This, along with the flood of Japanese swords into the market, drove price down somewhat. Regardless, they continued to be popular through the end of the Ming Dynasty. This rule was regularly ignored and subsequent trade missions contained tens of thousands of swords for trade.

“Regarding, the Bunmei 15 mission, there is a report of a Chinese official extant who complained that besides of the 3.610 swords brought as tribute, the Japanese had 38.610 swords on board as their official articles for trade. This was ten times the permitted number, so the then minister Zhou Hóngmó (周洪謨). Also we learn from the chronicles and tribute records that there were each time discussions between the Japanese and the Ming officials on the acceptance of the swords exceeding the 3.000 limit and the price they are bought for. And to bear the expenses of the bakufu, it was decided on Japanese side that the merchants had to pay tax for what they sold abroad. So the merchants were quasi forced to sell as many goods as possible to reach a certain profit margin which makes the missions attractive at all. But we know that even with these difficulties, the overseas trade, including swords, was quite lucrative.”-

Markus Sesko- “Japanese Sword Trade with Ming China”

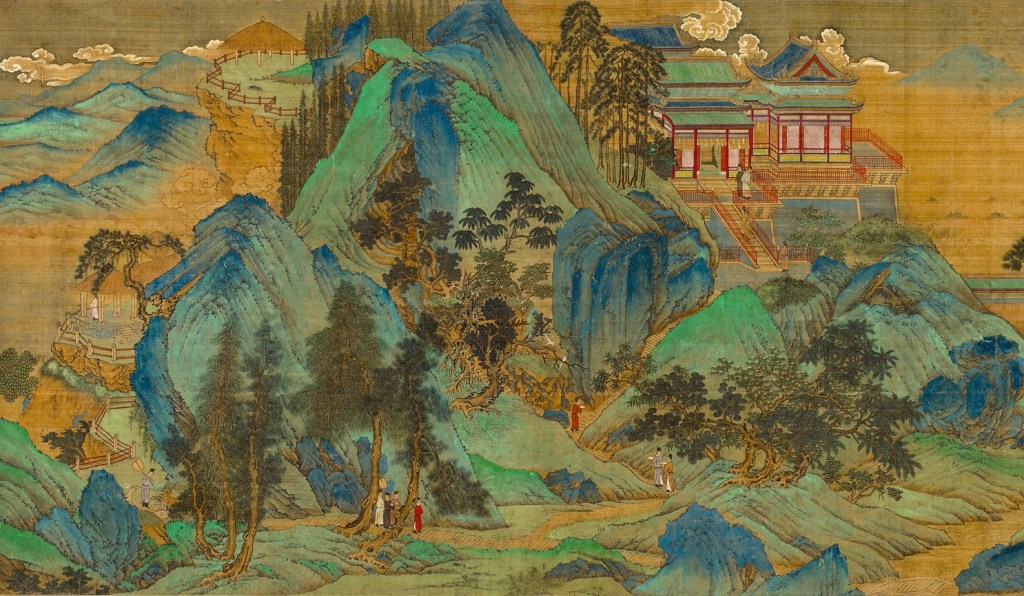

Collectors of the Ming

This is a lot of swords. Why so many? Besides the taxes and other practical business challenges, the Japanese merchants and traders knew that Japanese swords were quite the rage among Ming Dynasty collectors. One of the many reforms that the Ming empire made was a privatization of much its manufacturing and industry. This created several new classes of people that had not existed in Chinese society before. The rise of the Merchant class was reminiscent of the Han dynasty approach to such things. Wealthy merchants and gentry class started to have more contact. And the collecting and connoisseurship worlds broke open in a huge way.

The Ming is world famous for its art, architecture and furniture to this day. This was direct result of a robust collectors market of porcelain, paintings, poetry, and other objects of art. Swords were also among these items. Although, sword collecting was not without its controversies. The old confucian idea of the scholar warrior was being resurrected. However, at that time, the major interpretation of Confucius was that the martial and scholarly mode of life were treated as as two separate worlds instead of balancing forces. And the Martial areas of government were not held in esteem. So, some scholars and literati did not find the interest in military and martial art and artifacts worth while. Luckily for us, a great many did, and there are many accounts of collectors seeking and praising the workmanship and cutting ability of the Japanese sword.

It should be noted that looking at the numbers of swords brought in, it may be tempting to think of them as the Katana and Tachi we are used to seeing in museums and as modern reproductions. These were probably not of that level of craftsmanship. The bulk orders of swords may have been of more common quality found in the weapons of soldiers and guards. Certain soldiers may have had Japanese blades either in their full original fittings or given new Chinese style fittings of the time. Also, many of the wealthy merchants hired private security for their households. These guards could have easily been equipped with such weapons by their employers. But even with these more utilitarian swords, the sharpness, forging quality and quality of the furniture made the Japanese sword a much sought after and prized possession.

It should also be mentioned that most collectors and the collecting world at large in the Ming was very much enamored with the Jian. And talk of Jian and stories of prized Jian named for their legendary status dominate the discussion. Ironically, the Jian had fallen out of military service at least as far back as the Tang Dynasty, although it was still seen as a weapon of status and of lineage. Generals were presented with swords as symbols of their station. Most statues of military leaders or heroes from this time are depicted holding Jian. Jian had not completely left the battle field as civilian militias and boarder forces often used short heavy Jian as side arms for infantry and archers. The civilian market for Jian was also big and many beautiful presentation swords were created as well as functional weapons for polite collectors.

The Japanese swords are a bit different. Collectors enjoyed the Japanese swords for several reasons. The blades were forged well and reminiscent of the Tang Dynasty techniques that the Japanese took inspiration from and their fittings were well made and pleasing. The exotic nature of the blades was a draw as was the idea of taking a weapon used by the pirates of the coast when the Jianjing Crisis erupted. The popularity grew so much that Dao form Japan and/or done in the style of Japanese swords gained their own name; Wo Dao. Wo Dao is the collective term for Japanese style blade. In the late Ming, this could mean a fully Japanese sword with original fittings and blade. It could also mean a Japanese blade with Chinese style furniture and/or hilt assembly. And finally there are those swords that were simply forged with the same geometry in the blade but being of 100% Chinese manufacture.

Jianjing Crisis: Pirates!

The Ming Maritime restrictions and tribute process put considerable pressure on areas of the country that were more dependent on this trade. The East Coast of China during the reign of Jiajing Emperor (1521–67) was a major player n trade with the rest of Asia. Japanese, Korean, and Indonesian maritime trade bustled the region for the start of the Ming. Also, Western players like the Portuguese brought in precious metals like gold and silver. Silver was imported by the Ming in great quantities This brought the Portuguese into the picture to play a role most often over looked. Their involvement open the “Colombian Trade” in 1513. New world crops, precious metals and , importantly, guns were traded for numerous Chinese goods that were gaining popularity in Europe.

This created a huge amount of wealth for some people. Merchants benefited from the robust trade and fed the growing non-gentry class of wealthy people now engaging in lots of trade and exchange with other cultures. The cities along the coast became centers of commerce and of society. A new class of entrepreneurs and those taking advantage of the lais·sez-faire Ming taxation and commerce policies and the farmers in the outskirts were able to make a good living from the markets in town and the government projects that were geared toward increasing agriculture for the Dynasty. A good amount of prosperity was being had by several groups of people, all with different goals and values. The government, however, was going broke. It could not sustain the amount of expenditure that they had instituted. Naturally, the trade with other countries was one means they had to create some income. But, their efforts were not always a- well received and b-successful. The denizens of areas of heavy trade were constantly affected by changing policies. Frustration and greed on all sides began to brew. These would end up coming to a head in 1523.

When the Japanese made tribute missions to China, their designated point of entry was the city Ningbo in Zhejiang for official trade. This continued up until the Ningbo Incident of 1523. Internal Japanese conflicts between daimyo had spread and reached China. Two competing clans fought over the right to present tribute and thus trade with the Ming. This fight grew out of hand and over took the city. The Ming Navy was called in to restore peace, but was defeated by the Japanese traders that started the fight. The Japanese escaped back to their home and left the Ming Navy humiliated. From that point, the Ming banned all trade with the Japanese.

This left not only the Japanese merchants and “Sea Lords”, as they called themselves, out of the official trade system, but it had a major impact on the livelihood of the denizens of coastal cities. Merchants were of course hardest hit by the prohibition, and most of them simply defied the ban. Some them ended forming large smuggling and illegal import syndicates with the Japanese Sea lords and their men. The numbers of people affected but the ban on Japanese trade were so great, many them would become pirates themselves. Local corruption helped keep up appearances for a time, but soon it became one of the Ming dynasties most pressing problems and plunged the region into many years of bloody violence.

The entire area from Dengzhou to Guanzhou and into the Haikou area was beset by pirate raids. The “Wokou” 倭寇 as they were called, underscores the strange attitude and situation this crisis presented. The term, translated as, “Dwarf Pirate” is a racial slur, but one which was was used frequently. The word “wo” denoting the Japanese is however a bit misleading here. As the Crisis wore on, the majority of the raiders in these groups were local Chinese, not Japanese. The Japanese had found enough co conspirators to essentially out source much of the conflict.

This is the main reason that the ‘Jainjing Crisis” is such a pivotal and important event for modern martial artists.It represents a huge touch stone for Sino-Japanese exchange and therefore, provides much of the background for the arts we practice today.

Qi Jiguang

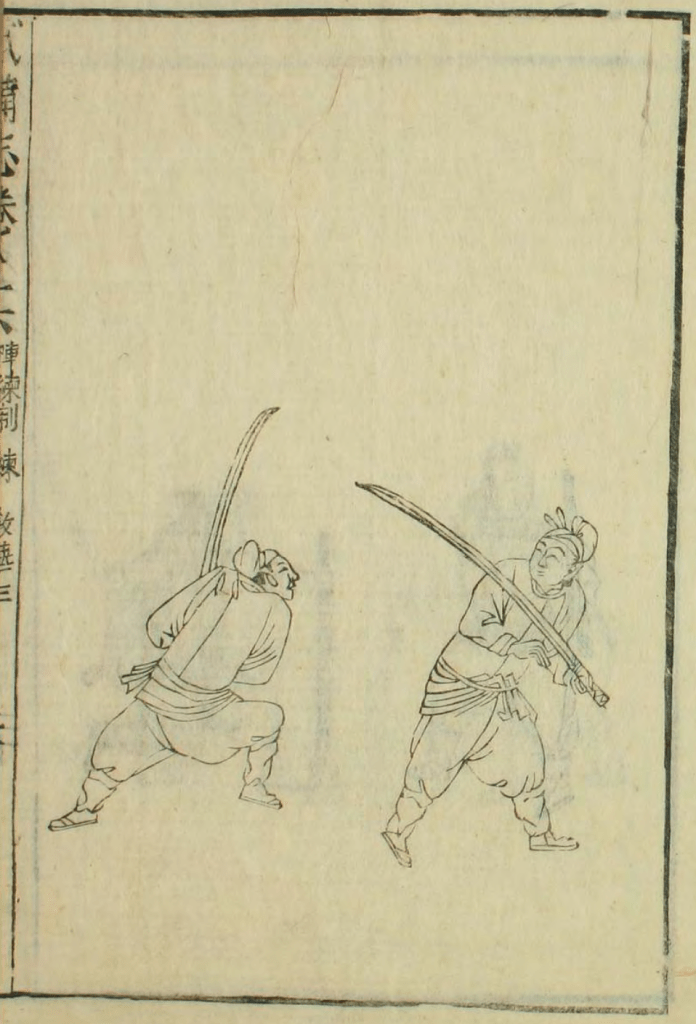

Enter the famous General, Qi Jiguang戚繼光. One of the patron saints of modern kung fu, Qi’s accomplishments are many and grand. However, he is often seen only in the light of the martial arts that he set downing his book Jixiao Xinshu練兵實紀. But, Qi was responsible for many changes that occurred not only in the military realm, but in the political, literary and social aspects of his time as well. But for this discussion General Qi serves a critical role in the dissemination of the Japanese sword in Chinese culture during the Ming.

When Qi arrived on the scene, the situation was bleak. The Wokou constantly beat back the weakening Ming forces, often by mere intimidation they were able to cause many the Ming soldiers to run away. This is mentioned by Qi himself and by many authors at the time. These encounters often entailed brandishing their Japanese swords in the sunlight, blinding the enemy and showing what good weapons they had. The Wokou also had many fire arms, mostly provided by the Portuguese who had superior arquebuses, and so out gunned the Ming forces by a good margin. The previous General, You Dayou had all but begged the Ming Court for more guns and ships to combat the Wokou threat. They refused. And in fact, some of the very same Portuguese guns were deployed on the Northern Boarder and not the coast.

They sent Qi Jiguang to help tame the situation. He identified a problem; the weapons the Japanese Pirates used were using were far superior than the Ming arms. Since he could not rectify this imbalance, he tried a different tactic. He would bring the fight to them in places where they could not readily use these advantages. In order to do this, he began to conscript troops, avoiding city dwellers and more affluent or mobile groups and concentrating instead on farmers and local rural populations. He devised squad tactics to fight more efficiently in the streets and fields of the area. And he delved in to using cold weapons like spears and shields in conjunction with firearms to help mitigate the lack of comparable guns. It was these tactics and theories that he devised during the Pirate Crisis that he recorded in his training manual. These tactics would also be used against the Mongols invading Beijing later in the century.

This also brought him in contact with Japanese swords and swordsmanship. The Wokou raiders were comprised of a variety of ne’er-do-wells, The Sea Lords were the leadership of the pirates and the self appointed Daimyo of the ocean. Something that the Ashikaga Shogunate and several ruling clans accepted, as it extended the influence of several warlords of the time. Many of the principle leadership of the clans/syndicates remained on the islands in the East and South China Sea as their base of operations. They coordinated with local Chinese and various Japanese ronin who did the bulk of the actual incursions. These ronin (masterless Samurai or mercenary) used the swords and swordsmanship of their native origin, thus bringing them into contact with General Qi and other Chinese. Both Wokou and not.

Qi identified two weapons that he incorporated into his method. The first was a side arm called a Yao Dao or “waist saber”. The second, along two handed sword familiar to modern audiences as a Odachi (great sword) Nodachi. (field sword). And Qi was not alone. Many military and civilian writer of the time commented and told stories of the highly polished blades shining in the sun and the leaping and active footwork of the Japanese swordsmen. The Wokou had gained a fearsome reputation not the least of which was their weapons, which by ming dynasty accounts, were visible superior to Chinese blades being manufactured at the time.

General Qi captured many weapons during the campaign on the coast. He was impressed by the design of the Japanese weapons and the quality their manufacture. In later days, after the Jianjing crisis, he commissioned sabers with these cross sections and specifications to incorporate into his forces armament. He deployed them in his famous “Mandarin Duck formation” as a back up to firearms and gun powder weapons. The long sword was employed by riflemen/musketeers primarily, but was also used in squad warfare as the “short weapon” as contrasted with the spear. The style he set down was not named, but in the Wubei Zhi, Mao YuanYi cited that it was created in the year of “Xinyou” and thus has earned the moniker “Xin You Dao”. The waist sword was paired with the shield and javelin. Qi himself thought the dao was useless without the shield but employed shield men armed with sabers and throwing spears to great effect. The “WoYao” dao Japanese style saber had been popular for a time before so Qi had already been using this weapon as the side arm for his troops. However, Qi became so associated with this design that sabers of these shapes are collectively called “Qi Jia Dao” or Qi Clan Sabers to this day.

Conclusion

Qi JiGuang earned a lot of fame for his success on the coast and in the northern boarder conflicts. And this only helped increase the popularity of the Japanese sword among collectors and military. But he was wasn’t the principle reason for this phenomena. The trend had begun ,as we have seen, with the first tribute missions to the Ming Dynasty by the Japanese. Its popularity among collectors and generals alike helped it enter the martial zeitgeist at the time in an important way. The influence is then seen in many, if not most, of the saber designs to follow. This popularity would continue well into the Qing Dynasty with many of the sword forms becoming set down in official Manchu military catalogs. The influence of the Japanese sword is readily apparent.

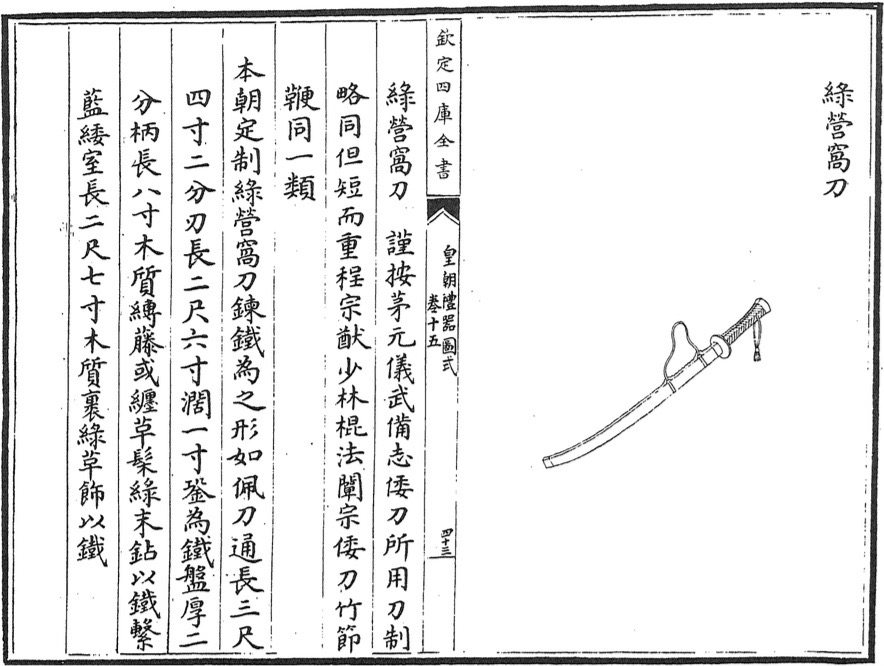

Translation by Peter Dekker: “According to:

Mao Yuanyi’s BOOK OF MILITARY PREPAREDNESS:

“Japanese swords: The ones they use can be summarized as being quite alike, short and heavy.”

Cheng Zongyou’s EXPLANATION OF SHAOLIN STAFF METHODS:

“Japanese swords, bamboo sectioned whips, they are the same.”1

The regulations of our dynasty:

Made of forged iron [as to produce steel], it is shaped like a peidao.

Overall 3 chi 4 cun and 2 fen long. (Approx. 120 cm / 47 inch)2

The blade is 2 chi 6 cun. It is 1 cun wide.

It has an iron disc guard that is 2 fen thick.

The handle is 8 cun and made of wood. It is either wrapped with rattan or in braided wrap with [strips of] leather, lacquered green. Iron pommel. It has a blue lanyard.

The scabbard is 2 chi 7 cun long, made of wood that is covered with green leather. It has iron fittings.”

The back and forth of trade and influence that China and Japan have enjoyed is very old. From the first visits by dignitaries to the later Han and then the Sui and Tang Dynasties to the Pirate raids of the Wokou, the two cultures have both been instrumental in the other’s development. Just as Japan exported Copper that was then minted into coins that were imported back to Japan, China had exported sword making technology and inspiration only to have it return 500 years later. By the time of the Ming, so much of the earlier culture of swords and been diminished, many of the techniques for using cold weapons were thought lost. It is near the end of the Ming that scholars and generals looked with seriousness and purpose to the surrounding kingdoms of Korea, Tibet, Vietnam, and Japan for remnants of these practices. Often finding them in some form.

There is much tribalism that occurs in the martial arts today. So much of that is based in past events and the spin that generations of teachers and students have placed on those events. But it is out fortune that we are situated and far removed form the reality of sword combat and death by steel. We have a birds eye view of what came before in a way our forebears had not. They have left writing and artifacts, but even those can be foiled in passing on their stories. Many martial artists hold some rivalry between Japanese and Chinese arts. Some talk about how Japanese arts and weapons were imported form China. Or vice versa. Some will claim either is superior to the other. But these are frivolous questions that lead to no real insight. The truth as always, is far more complicated and interesting. China and Japan have had a long and close relationship that has changed both. These connections can be things that bond us through understanding.

As we always say here at TPLA; the arts like us, are more alike than they are different.

Further Reading

Japanese Trade missions to Tang China: https://aboutjapan.japansociety.org/the_japanese_missions_to_tang_china_7th-9th_centuries

Excellent Article on the various types of Saber in the Qing many of which are directly taken form the Japanese: https://www.mandarinmansion.com/article/chinese-long-sabers-qing-dynasty

Di Cosmo, Nicola, ed. Military Culture in Imperial China. (Ryor, Kathleen, Wu and Wen in Elite Cultural Practices During the Late Ming) Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2011, ©2009.

He, Yuming. Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series. Vol. 82, Home and the World: Editing The “Glorious Ming” with Woodblock Printed Books of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Asia Center, 2013.

Shapinsky, Peter D. Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies. Vol. 76, Lords of the Sea: Pirates, Violence, and Commerce in Late Medieval Japan. Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan, 2014.

Tong, James. Disorder under Heaven: Collective Violence in the Ming Dynasty. Stanford University Press, 1991.

3 thoughts on “Katana to Dao part one: Saber and Coin: The Japanese Sword in the Ming Dynasty”