The idea has often been advanced that that almost no one ever parried with their edge in combat in Chinese swordplay. One type of evidence presented for this is that there is, supposedly, no evidence of edge damage from parries on historical examples of Jian that exist today. Which leads us to these questions: Why would there be no edge damage on swords if they parried with the edge? How could a sword that was used by a soldier not have edge damage on it? If there are no examples of edge damage on Chinese swords, how can we say that edge parries existed in Chinese swordplay?

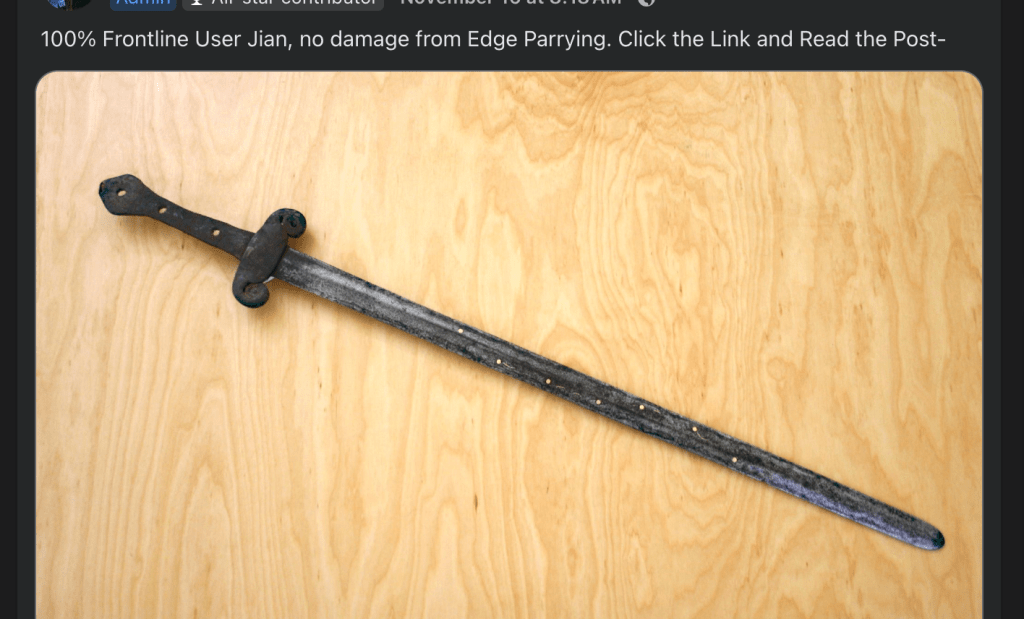

(A comment on the above picture) “NOTE: There is No Evidence of Edge on Edge Parrying on this Blade. No one has presented even a single example of a Chinese sword with edge damage indicative of edge parrying.

If no actually (sic) physical evidence of something can be found after examining literally thousands of swords, then It is extremely unlikely that it was common or even happened. If it did, where is (sic) there would be physical evidence.”

There are several problems with this line of thinking. Both logically and practically. To begin with, “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence”. Even if we accept that there are no examples of edge damage on Chinese swords (a dubious observation its self) that in no way can allow us to draw the conclusion that edge parrying was completely absent from sword techniques in the Chinese arts.

Why would there be no examples of historical Chinese swords with edge damage from parries if they were used?

Probably the most salient of reasons is one of “survivorship bias”. Swords that are used, contrary to popular belief, get damaged fairly easily. Especially in warfare, or environments that contain a lot of swordplay, edges will almost immediately dull and become nicked. Blades break, fittings become loose or damaged, handles fall apart. If by some miracle you survive a few encounters and your sword received damage to the blade, you are going to repair it. Either by sharpening the nicks away or having a blacksmith do more extensive repairs. But you will not simply keep your edge dinged up as we do our practice weapons today. . On a battle field, most damaged weapons were probably repaired, taken to be reforged into new weapons, or left on the ground to rust away to dust. Every now and then a big cache of weapons are found that had somehow been preserved, but these events are relatively rare and always cause for celebration among academics and collectors. The direct effect of this is that damaged swords don’t get preserved as much as undamaged ones and the ones that do survive are almost always repaired or brought back up to standards.

This is exacerbated in the Chinese arsenal with the “Great Leap Forward” , and the movement to reclaim steel and iron for use by the government in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s. This lead to thousands of backyard furnaces manned by regular people who had no experience or knowledge of metallurgy, forging techniques, or any thing related to harvesting iron from steel. This resulted in untold numbers of old swords, tools, and weapons being melted down into worthless pig iron. This is why many surviving swords today are shorter, smaller, or more ornate – basically, swords that are either easy to conceal and hide or others that people would be highly motivated to hide from those wanting to melt them down. The ins and outs of this bias are out of the scope of this discussion, but one can imagine the effect. The bottom line to this question is that there is conceivably a larger hole in the historical record than is being admitted by the argument that there is no edge damage found..

All this creates a bias in the historical samples and records of surviving swords. It also omits the data on how swords failed and why. For example; if there is a flaw the allows one type of damage to occur in a particular type of weapon, and that damage renders the weapon unusable, any weapon that receives that damage will be under represented in the surviving artifacts. If not enough examples of swords destroyed in this way are saved, modern collectors and historians will have no knowledge of this flaw unless it is recorded in writing. Therefore, even the lack of edge damage would not support a conclusion that edge parries were never used. It would need to be cross referenced with some sort of textual evidence or written source.

To say that there are zero examples of such damage would require us to know that we have a near complete record of every culture, school, style, and context of Chinese swordsmanship with an unimaginable number of swords to examine. The fact of the matter is, we have a very small number of the swords that were used by people of the time. Even in Europe, where castle armories brim over with old weapons, these represent a dwindling minority of the swords that were used in history. As you approach the modern era, more and more swords survive. This is a result of the proliferation of fire arms and the changing face of warfare. Even some service weapons of the 1800’s would rarely be used in combat and even less frequently against other swords. Some where not even sharpened.

Can you reasonably expect to find zero damage to edges on historical swords that were used?

Even if we grant the unlikely premise of a universal ban on edge parrying, that in no way prevents edge damage from appearing on artifacts. And that damage can be all but identical to parry damage. Hitting shields, armor, fasteners, even bone or any other object they might encounter can create rolls, dings and nicks. Mistakes happen, even if one is thinking of avoiding edge contact, there will inevitably be some. Not every person who is using a sword in history is an expert swordsman. Some are simply soldiers, some criminals, and some are regular folks that just have one for self defense. Are we to believe ALL of these people in all time periods were all expertly able to avoid parrying with the edge and damaging any of these swords?

If avoiding edge parries is a thing that is taught, there will be a learning curve. People learn things over time and at the beginning, they are going to mess up. So even then, we would need to see edge damage from parries in the less advanced swords-people. If your strike is parried with the edge by your opponent, that still affects your weapon. So even if you are a sword saint with impeccable skill, if your opponent is just some shlub who is hacking away at everything, they are going to cut into one of your attacks eventually, and both weapons will have edge damage. Edge damage seems to be unavoidable.

Is it practical to parry with the flat only?

Which brings us to the next point of contention; anatomy and practicality. There is a reason swords are designed the way they are. They take advantage of our biomechanics to create a labor saving device. As such, the edge of the weapon is situated in the position that gives us the most stability to produce force with our arm and hand. This is the same plane of motion as a throw, a hammer swing, or cutting and sawing. The intuitive action with a sword is to lead with the edge. This is the plane that it is the most strong and stable, it allows us to brace for the impact, and it is our natural motion to stop something. People need to be taught not to do this. Even if the prohibition existed in swordplay in China, that does not preclude edge damage from being present on weapons. And figuring out how that damage occurred is not a simple matter.

Is there really zero evidence of damage from edge parries?

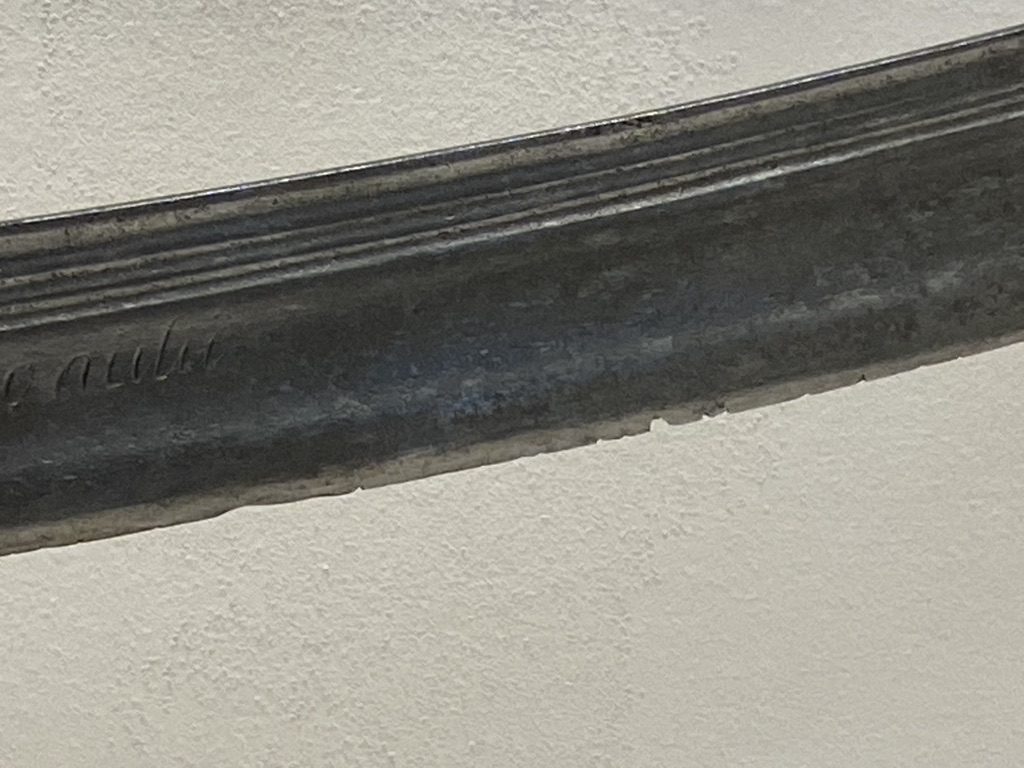

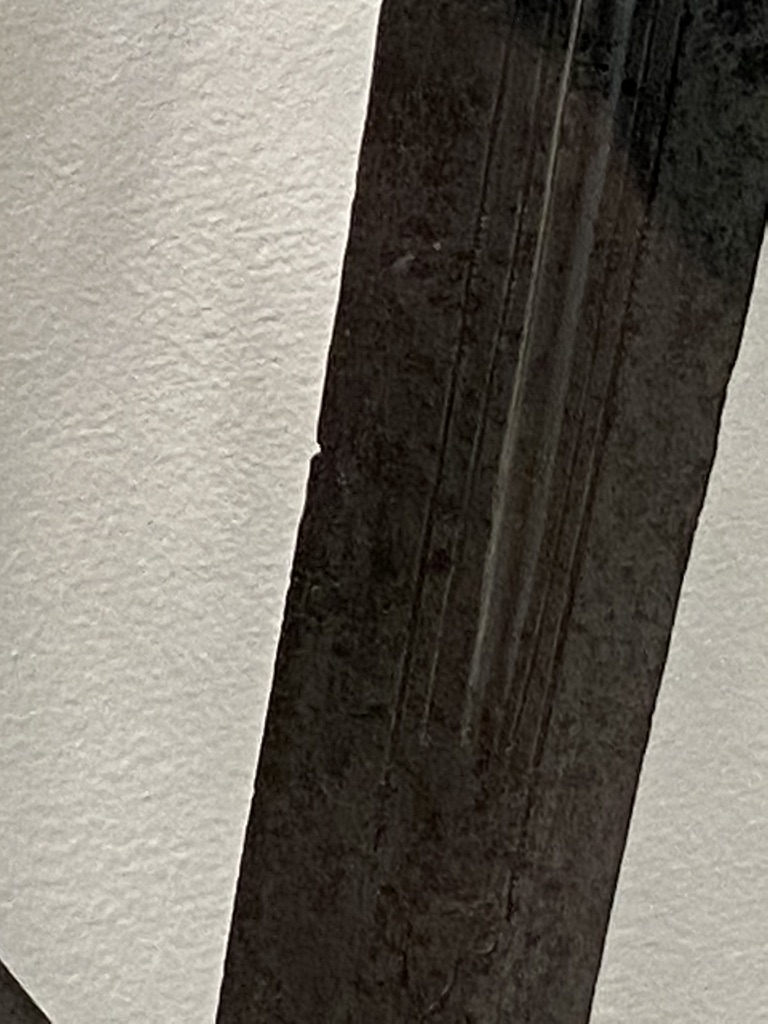

The claim that Chinese swords do not show evidence of edge damage from parries is one that seems to be contradicted. There are many examples of weapons that have edge damage and much of the damage could easily have been done by edge to edge contact with another sword. So some unstated qualification is being made. What constitutes damage from edge parries specifically? What criteria are being used to determine what is edge damage from parries and damage from other things? Even in photos available on the internet, one can find edge damage that very much looks like parry damage. Admittedly, I am not an expert on these artifacts and am only going on examples found in image searches. But, talking with experts like Peter Dekker of Mandarin Mansion, it would appear that all forms of edge damage can be found. that includes chipping, rolling, and cuts into the edge. I am skeptical that one can discern that much about the cause of the damage from looking at the examples of that damage alone. What chipped this edge? Another sword, or did the owner drop it one day while showing it off? Who can tell? Depending on the type of damage, it may be impossible to know for certain.

It is also ignores discussions of flat damage. If the flat was used exclusively for parries, would that not result in extremely marred up surfaces? After all, if we expect to see lots of edge damage in surviving artifacts, why not expect damage to the flat? In practice weapons which do not have sharp edges, the flat of the blades become scraped, dinged, and cut into very noticeably. If edges were never used defensively in Chinese swordplay, should we not see more damaged flats? And if the distinction is between European and Asian methods, should not the Asian, or at least the Chinese, swords be replete with more flat damage than their counterparts from different parts of the world? Again, I am not an expert collector of swords, but to my eye, that has never jumped to at me as a big difference between such artifacts as seen in museums and photographs.

Where did this idea come from anyway?

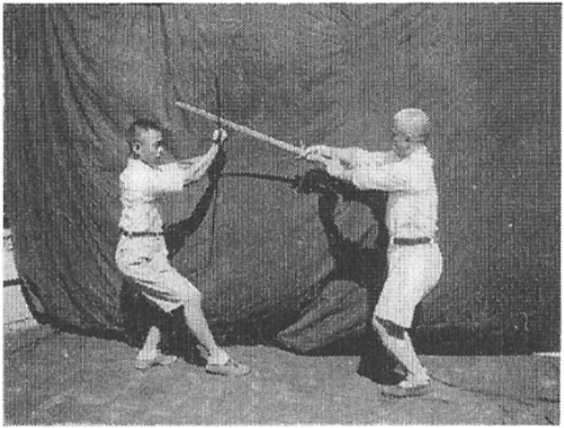

The question of did Chinese swordplay include a prohibition against parries with the edge is also one that is difficult to rationalize. Did Chinese swordsmen have a prohibition on edge parrying? Not in the literature, it would seem. I have not been able to find any historical document about swordplay from the Chinese tradition that explicitly forbids edge parries in all circumstances. And even then, that would be one school out of hundreds, far from being universal. In the existing literature, there are instructions to use both the flat and the edge. Photos from the turn of the 20th century show swordsmen performing edge parries to both edges and flats. Two person forms often have edge to edge parries included in them. The view of “no edge parries” paints Chinese swordsmanship as a monolith, not taking into account the vast numbers of different schools and methods that have arisen over time and area.

History and Mystery

Finally, we have no way of knowing, most of the time, how or even if a sword was used in battle or actual duels. Unless we have a pedigreed story of it, we are usually left to wonder who owned a certain sword and how or if they used it. Many could be used for practice or just fooling around by scholars or dilettantes. Militia Jian which have “seen combat” as it is said, would often not be paired sword to sword but rather as a side arm to use with firearms or against spears and other long weapons. These weapons would be less likely to have lots of damage as, even in combat, they might never be drawn.

Conclusion

In conclusion, using the supposed absence of edge damage on historical swords is not a good argument to defend the claim of a complete absence of edge parries in Chinese Swordsmanship. Nor is it very convincing evidence of the type of techniques used with swords in the past. So many of the swords that survive into the our time were either not used for fighting or have been repaired, giving a false sense of the normal damage incurred by the weapon. The claim that there is no such edge damage on any examples of historical swords is also contradicted by photographic evidence. Damage is visible but there is no reliable way to tell exactly how that damage occurred without witnessing it. So even the claim that there is no edge damage due to parries on historical swords is false. Add to this the there is no apparent textual evidence in manuals, stories or other sources that explicitly deliver the prohibition of parrying with the edge. Most sources don’t mention it or give instructions for both. Photographs from the early 1900’s show both being utilized, which seems to contradict the claim.

Until some textual evidence that edge parries were completely forbidden in all sword arts in China I don’t see any reason to conclude that Chinese sword arts or weapon development deviates from the practical and logistic patterns as other arts around the world. Differences can be observed in the cultural divergence between traditions, but this claim seems poorly constructed. I don’t find it hard to believe that folks who paid for their own swords would be more delicate with them and probably avoided edge to edge contact as much as possible, but again, that doesn’t really support the claim of a universal ban.

The same claim circulated in the HEMA community for years. Eventually, reason won out and that view point has fallen into the minority. Now the argument is used to distinguish Chinese and Western styles. We are to believe that edge parries were used in Europe but not China. To bolster this claim, the claim that no edge damage from parries on historical examples is presented. But, there is damage that might be from parries present on some historical examples. So what is the qualification being made here? I fear it is some version of a True Scotsman argument about how true Chinese sword art does not use the edge to parry and that any evidence of such damage can be chalked up to some manner of deviation from tradition. Or some obscure qualification is being made to move the goal posts as to what type of damage is being considered as edge parry damage.

In the end, the discussion of if there was a ban on edge parries in Chinese arts is less important than the practical considerations of modern practice. For historical perspective, sure, its good. But as a guide to practice, that is not always the case. It would also seem that edge damage is unavoidable. The absence of it would seem to indicate the weapon was never used, or was repaired. So as for the evidence that edge parries were universally forbidden, I feel we need some corroborating textual evidence that shows not only that it was forbidden, but widely forbidden independent of school or style. If such evidence exists I have not had the chance to see it.

For a more technique based look at the parry check out S-words: Ge.